The blog post was originally written about three years ago for another website. However, it’s all still relevant today (May 2017). Since writing this piece I’ve been involved with setting up a much larger system which presented a few additional problems, I’ll post an update at some point with some more pointers.

Having set-up my own VOIP (Voice-over-IP) phone system I thought I’d share what I’d learned. Here’s the basics of setting up your own system, including some of the problems you might encounter.

Apparently I have a bit reputation amongst my colleagues for being a true Yorkshireman when it comes to spending money. In other words, I try and avoid it. Every couple of years I thoroughly enjoy reviewing all of our overheads to see where I can trim a few bob. Just lately I turned my attention to our phone system. When we moved into our offices I didn’t know much about VOIP (Voice over IP, or Internet telephony) or what you could do with a VOIP system (other than making and receiving phone calls). Our old system was supplied in an off-the-shelf configuration and we couldn’t really do much more with it than with our previous analogue Centrex system.

I started tinkering with a couple of old VOIP phones to see if I could extend the system and add more functionality to it. It was a steep learning curve but I’m now confident enough to implement our own system.

Before you jump in

Before you consider printing off this blog post, cancelling your telco contract and buying your own VOIP kit, consider this:

- If it doesn’t work have you got the IT skills to figure it out yourself?

- If it breaks do you want to be able to call someone to fix it?

- If you’re on old analogue lines will your broadband support the number of VOIP telephone lines you need?

- If your broadband line gets a pneumatic drill put through it, how will you cope with losing all of your comms at a stroke?

If any of these sound like they’ll destroy your business or your sanity, then don’t read any further! I probably also ought to point out at this stage that while I’m happy to get comments on my blog postings, comments of the “I did what you said but now my office has ground to a halt and I’m about to get fired so please ring me and tell me what to do NOW” variety are not welcome. It’s your risk, OK?

Bandwidth

It’s essential your broadband is fast enough to support as many simultaneous calls as you need. The bandwidth requirements vary with different factors such as which audio codec is used. Worst case scenario is that one call will use 80kbps (or 0.08Mbps) in each direction. Broadband speed is usually slower on the upload side so work from that. If you have a basic 0.5Mbps upload speed you’re going to max out at six calls – in practice it will be less than that because of other traffic on the broadband and contention from neighbours.

The basics

There’s three basic ways to get a VOIP system:

- Get a telephone company to do it for you. We did that but we didn’t get all be benefits of VOIP and it cost as much as tradition phone lines.

- Set up an in-house VOIP server (such as Asterisk) and hook it up to a SIP trunk provider via your broadband. I thought that was overkill.

- Set up an account with a cloud-based provider of SIP accounts.

I’m going to describe what’s involved with the third option.

Buying handsets

There are three main consideration for selecting your handsets: protocol, ports and power.

Protocol. There are a variety of different protocols used by different VOIP phone systems, but for our purposes we want phones that speak the common SIP protocol. Before you buy handsets check that they support SIP. Some handsets support more than one protocol, or can be changed from one to another with a firmware update (although this can be a bit tricky – as I’ll explain later).

Ports. Your phones need an internet connection using a standard ethernet cable to a port on your router (possibly via a switch). Have you got enough network ports to plug all your phones in? Some handsets have a network pass-through on them – you plug the phone into the network port and then plug a desktop or laptop computer into the back of the phone, meaning you don’t need as many ports on your router.

You can get VOIP phones that work over Wi-Fi, but they’re more expensive and I don’t trust Wi-Fi enough to consider this an option. (Edit May 2017: I still don’t)

Power. Many VOIP handsets don’t come with a power adapter to plug it into the mains. Instead they rely on power coming down the network cable using Power over Ethernet, or PoE. If you want to use PoE your phones will all need to be plugged into a PoE router or switch. If you don’t have/get a PoE switch you’ll need to buy additional power adapters, which can cost as much as the phone itself.

PoE delivers power over standard CAT5 networking cables. Image courtesy nrkbeta.

We already have our own PoE switch that powered our old VOIP phones, and of course they were all networked, so going for PoE again was the simplest and cheapest option for us. Remember that if you go for PoE your router or switch could be a single point of failure. When we set up the first VOIP system I decided that we ought to have a spare PoE switch ready to go in case one failed.

I managed to pick up an unused 3Com 24 port switch for £88, which is still going strong, and I bought a used Nortel switch for £55 as a back-up (both from ebay). For a modest setup, expect to pay about £40 for a basic PoE switch which can be added to an existing network.

In deciding which handsets to buy, I looked on ebay for phones that seemed to be quite common, on the basis that I didn’t want a bunch of different makes and models to puzzle over. I googled the model numbers to check they support SIP and to get an idea of how easy they are to configure. The website http://www.voip-info.org/ was really useful for this.

I found that the cheapest phones generally only supported proprietary protocols, so ruled those out. I found lots of Cisco models (sometimes under the Linksys brand) that can support SIP but I know from experience these usually come configured for the proprietary SCCP protocol and require a firmware update to convert to SIP, and are generally a pain to configure unless you have a Cisco support contract. I also ruled out any models that didn’t have a web management interface (this lets you set up the phone by connecting to it from a web browser).

The result of this process was that I bought five unused LG Nortel LIP-6812 handsets from eBay for a grand total of £51 including postage, which I was pretty pleased with. Although these are a few years old, they were still boxed like new with manuals, making the setup easier. If you buy phones without paper manuals, make sure you can find the manual online first.

Commissioning

The first thing you need to do is plug in your phones and make sure they power up and you can bring up their web management interface in a browser. If you have gone for the PoE option, and nothing happens when you plug them in, make sure you’ve connected them to a PoE port on your switch/router – many switches have a set of PoE ports and a set of non-PoE ports on them.

Most phones will come configured to use DHCP to pick up an IP address on your network automatically. If not you’ll need to work out how to put the phone into DHCP mode or assign it a suitable IP address via its front panel (both outside the scope of this post).

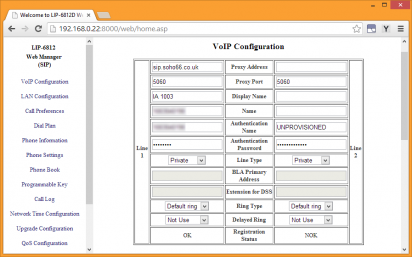

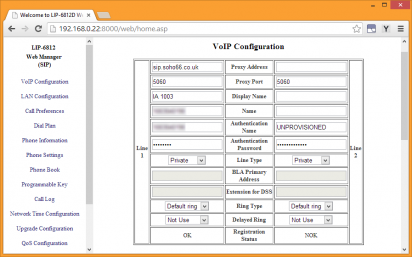

To be able to bring up the web management interface, you need to know the phone’s IP address. You might be able to get this by looking at the “connected devices” or “DHCP leases” information in your router’s own management pages, or from the LCD display of the phone by going through the “settings” menu. With some phones you just put the IP address into a browser to bring up the management pages, but some phones will use alternative port numbers. For example the LIP-6812 management pages are hosted on port 8000, so the address you put in the browser is something like http://192.168.0.10:8000/.

Configuring VOIP settings using the phones web management interface.

There will generally be a username and password required to access the management pages. The default credentials will be given in the manual and/or on the label on the bottom of the phone. If the phone has been used before and the credentials have been changed, you might need to do a factory reset on it (which isn’t a bad idea anyway as it will clear out any old settings).

Once you’ve got power and access you’re ready to set up the connection to the SIP service provider – so it’s time to open an account with one.

The provider I chose was Soho66*. Their offering was much cheaper than our old provider and yet had all the features we needed and more – enough to satisfy my tinkering craves. They also have very good reviews on sites like Trust Pilot. Before signing up I confirmed with them that they were able to port in our existing phone number. They assigned me another new phone number when I signed up, so I was able to test both incoming and outgoing calls before committing to the number port.

The basic information any provider will give you is:

- SIP Proxy address – this is the IP address or domain name of the SIP server.

- User name – you’ll get one per extension.

- Password – to go with the above.

- Voicemail extension number – useful if the phone has a voicemail button.

You’ll probably find a myriad of settings in the phone’s web management pages, but these are the basics you need to get connected and I found leaving all the other settings in their default configuration was the best course of action.

Put the settings from your provider in and reboot the phone. After a minute or two it should connect with the proxy server and you can try ringing it.

I ran the following tests to confirm everything was working to my satisfaction:

- Dialling in rings all extensions (I set up a hunt group on Soho66’s excellent control panel).

- Dialling out works and presents the right caller ID to the recipient.

- Phones left idle stay connected for more than a few minutes (the phone has to periodically refresh its connection with the proxy).

- Calls can be forward between extensions, including in round-robin fashion back to the original line (something our old system couldn’t manage).

- Leaving a voicemail causes the red light on the phone to blink.

- The messages button connects to the voicemail service.

With some bargain hunting and a bit of luck, a five line system could be set up with a budget of £95:

Phones: £50

PoE Switch: £40

First months line rental: £5

Although we’ve got more lines, our set-up and first month line rental was still less than what we paid for two months line rental with our previous provider, and we’ll save a tidy amount in subsequent months.

Here be Monsters

It wasn’t all plain sailing. I came across a few problems whilst setting up the phones. One of the handsets wasn’t set to SIP mode and had to be flashed with newer SIP firmware. This involved:

- Finding the firmware online.

- Setting up some TFTP server software to deliver the firmware to the phone.

- Wrestling with our domain servers Group Policy, so I could set the Windows Firewall settings so the TFTP server was accessible over our network.

- Setting up our DHCP server to tell the phone the address of the TFTP server.

Fortunately I’d been through most of the pain of this previously getting our Cisco handsets working, so I was somewhat prepared for this.

The phone’s management interface has an option to upload a CSV file to populate the speed-dial phone book. Inexplicably, I couldn’t get this to work with either Firefox or Chrome, but it did work with Internet Explorer 9.

Be prepared to have to get stuck into these sorts of problems if you take the DIY approach.

Summary

Although a bit of research and experimentation was required, I’ve wound up with a phone system that’s cheaper, more flexible, has more features and is under my control. It’s not for everyone – and as I stated at the top, if you can’t get your phone to work don’t call me! However I hope I’ve shown that with a small outlay you can at least give it a try. If you succeed or otherwise, please let us know your thoughts in the comments.

* Disclosure: The Soho66 link is an affiliate link – if you found this article useful I’d be grateful if you used it to check them out.